String interning in Go

String interning is a technique of storing only one copy of each unique string in memory. It can significantly reduce memory usage for applications that store many duplicated strings.

The built-in string is represented internally as a structure containing two fields. Data is a pointer to the string data and Len is a length of the string:

type StringHeader struct {

Data uintptr

Len int

}In Go strings are immutable, so multiple strings can share the same underlying data:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"reflect"

"unsafe"

)

// stringptr returns a pointer to the string data.

func stringptr(s string) uintptr {

return (*reflect.StringHeader)(unsafe.Pointer(&s)).Data

}

func main() {

s1 := "1234"

s2 := s1[:2] // "12"

// s1 and s2 are different strings, but they point to the same string data

fmt.Println(stringptr(s1) == stringptr(s2)) // true

}Most of modern programming languages including Go intern compile-time string constants:

s1 := "12"

s2 := "1"+"2"

fmt.Println(stringptr(s1) == stringptr(s2)) // trueBut strings generated at runtime are not interned:

s1 := "12"

s2 := strconv.Itoa(12)

fmt.Println(stringptr(s1) == stringptr(s2)) // falseImplementation #

To implement string interning we need a data structure representing a pool of strings. The pool needs to support two operations: adding a string to the pool and retrieving a string from the pool. A good candidate for the requirements is a hash map:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"strconv"

)

type stringInterner map[string]string

func (si stringInterner) Intern(s string) string {

if interned, ok := si[s]; ok {

return interned

}

si[s] = s

return s

}

func main() {

si := stringInterner{}

s1 := si.Intern("12")

s2 := si.Intern(strconv.Itoa(12))

fmt.Println(stringptr(s1) == stringptr(s2)) // true

}Let's take a look at a few examples where interning could be useful.

Example 1: Text processing #

Lexers, parsers and other text processing tools can greatly benefit from storing only distinct string values in memory.

The following program reads George Orwell's novel 1984 from a file and tokenizes it into a slice of words for further processing:

package main

import (

"bufio"

"log"

"os"

)

func main() {

f, err := os.Open("1984.txt")

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

defer f.Close()

scanner := bufio.NewScanner(f)

scanner.Split(bufio.ScanWords)

var words []string

for scanner.Scan() {

words = append(words, scanner.Text())

}

if err := scanner.Err(); err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

log.Print(len(words))

}The book contains 103549 words, the length of all words combined is 483016 bytes. It's important to note that the number of unique words is much smaller - 15585.

If we take a look at a part of the words slice we can see the same words (IS in our example) having different addresses in memory:

fmt.Println(words[1111:1120])

for _, word := range words[1111:1120] {

fmt.Printf("%x ", stringptr(word))

}

[WAR IS PEACE FREEDOM IS SLAVERY IGNORANCE IS STRENGTH]

^ ^ ^

c0000159fa c0000159fe c000015a00 c000015a05 c000015a0c c000015a10 c000015a17 c000015a20 c000015a28

^ ^ ^Let's modify the program to use string interning:

package main

import (

"bufio"

"log"

"os"

)

type stringInterner map[string]string

func (si stringInterner) InternBytes(b []byte) string {

if interned, ok := si[string(b)]; ok {

return interned

}

s := string(b)

si[s] = s

return s

}

func main() {

f, err := os.Open("1984.txt")

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

defer f.Close()

scanner := bufio.NewScanner(f)

scanner.Split(bufio.ScanWords)

si := stringInterner{}

var words []string

for scanner.Scan() {

words = append(words, si.InternBytes(scanner.Bytes())) // intern words

}

if err := scanner.Err(); err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

log.Print(len(words))

}Now the words slice consists of strings that point to the string intern pool. All instances of IS have the same address in memory:

fmt.Println(words[1111:1120])

for _, word := range words[1111:1120] {

fmt.Printf("%x ", stringptr(word))

}

[WAR IS PEACE FREEDOM IS SLAVERY IGNORANCE IS STRENGTH]

^ ^ ^

c000015220 c0000146c8 c000015223 c000015228 c0000146c8 c000015230 c000015237 c0000146c8 c000015240

^ ^ ^The amount of memory required to store the words decreased from 483016 to 119628 bytes which is more than 4x reduction.

Moreover, the []byte map key optimization helps to avoid expensive heap allocations. The Go compiler recognizes si[string(b)] and performs the lookup operation without allocating a new string and producing garbage.

Example 2: Network services #

Another example where string interning can be useful is network services. Interning can be applied to some string responses from databases, gRPC or HTTP servers.

The following snippet caches user information after querying it from a database:

type user struct {

ID int

Country string

}

type userService struct {

db *sql.DB

cache sync.Map

}

func (us *userService) get(id int) (*user, error) {

if u, ok := us.cache.Load(id); ok {

return u.(*user), nil

}

u := &user{}

row := us.db.QueryRow("SELECT id, country FROM users WHERE id=?", id)

if err := row.Scan(&u.ID, &u.Country); err != nil {

return nil, err

}

us.cache.Store(id, u)

return u, nil

}There are about 200 countries as of December 2018, so storing only a single copy of each string can save us memory if the number of users we want to keep in cache is large.

The user service is called from an HTTP handler, which means the intern pool is required to be safe for concurrent access from multiple goroutines. Luckily Go 1.9 introduced a concurrent map - sync.Map.

The user service using a thread-safe version of stringInterner:

type stringInterner struct {

sync.Map

}

func (si *stringInterner) Intern(s string) string {

interned, _ := si.LoadOrStore(s, s)

return interned.(string)

}

type userService struct {

db *sql.DB

cache sync.Map

si stringInterner

}

func (us *userService) get(id int) (*user, error) {

if u, ok := us.cache.Load(id); ok {

return u.(*user), nil

}

u := &user{}

row := us.db.QueryRow("SELECT id, country FROM users WHERE id=?", id)

if err := row.Scan(&u.ID, &u.Country); err != nil {

return nil, err

}

u.Country = us.si.Intern(u.Country) // intern country

us.cache.Store(id, u)

return u, nil

}Usage in Go standard library #

The Go standard library uses interning in a few places, one of them is net/textproto. textproto.Reader interns common HTTP headers (Content-Type, Host, User-Agent, etc.) to avoid memory allocations.

String comparison #

A decrease in memory usage is not the only advantage of string interning. Interned strings can be compared for equality in constant time. All the compiler needs to do is to check if two pointers are equal (Go source code) instead of going through the characters:

TEXT cmpbody<>(SB),NOSPLIT,$0-0

CMPQ SI, DI

JEQ allsameI created a benchmark to see the performance difference between interned and non-interned strings:

package main

import (

"strings"

"testing"

)

func benchmarkStringCompare(b *testing.B, count int) {

s1 := strings.Repeat("a", count)

s2 := strings.Repeat("a", count)

b.ResetTimer()

for n := 0; n < b.N; n++ {

if s1 != s2 {

b.Fatal()

}

}

}

func benchmarkStringCompareIntern(b *testing.B, count int) {

si := stringInterner{}

s1 := si.Intern(strings.Repeat("a", count))

s2 := si.Intern(strings.Repeat("a", count))

b.ResetTimer()

for n := 0; n < b.N; n++ {

if s1 != s2 {

b.Fatal()

}

}

}

func BenchmarkStringCompare1(b *testing.B) { benchmarkStringCompare(b, 1) }

func BenchmarkStringCompare10(b *testing.B) { benchmarkStringCompare(b, 10) }

func BenchmarkStringCompare100(b *testing.B) { benchmarkStringCompare(b, 100) }

func BenchmarkStringCompareIntern1(b *testing.B) { benchmarkStringCompareIntern(b, 1) }

func BenchmarkStringCompareIntern10(b *testing.B) { benchmarkStringCompareIntern(b, 10) }

func BenchmarkStringCompareIntern100(b *testing.B) { benchmarkStringCompareIntern(b, 100) }The speed of comparison of interned strings remains constant independently of the number of characters:

BenchmarkStringCompare1-4 500000000 2.93 ns/op

BenchmarkStringCompare10-4 300000000 6.21 ns/op

BenchmarkStringCompare100-4 100000000 13.2 ns/op

BenchmarkStringCompareIntern1-4 1000000000 2.60 ns/op

BenchmarkStringCompareIntern10-4 1000000000 2.60 ns/op

BenchmarkStringCompareIntern100-4 1000000000 2.60 ns/opConclusion #

String interning can save memory at a cost of CPU time - every lookup from the intern pool requires hashing the input string (which may not work for CPU bound applications).

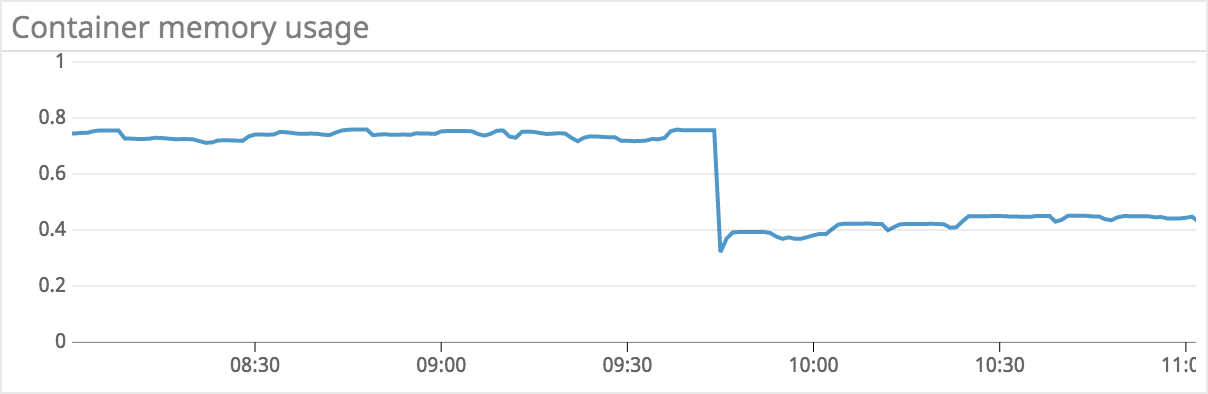

Here is a real-life example - memory usage of the application went down from 70% to 45% after I deployed a new version with string interning enabled: